Incident Management Matters - Archive

An irregular blog with thoughts and challenges on all aspects of Crisis Management, Emergency Preparedness & Response, Incident Risk and anything else that comes to mind.

COVID and Crisis Management

In the UK the first Module of the statutory enquiry into the Covid 19 pandemic, on the resilience and preparedness of the United Kingdom, was published last week. It contains findings and recommendations which the wider Crisis Management would do well to read. Many of the conclusions of this Covid report should resonate for any Emergency Planning professional.

I have pulled out some which I think are relevant across all sectors below, but you can read the full report here: https://covid19.public-inquiry.uk/documents/module-1-full-report/

First of all, the Findings:

- The UK prepared for the wrong pandemic. … preparedness was inadequate for a global pandemic of the kind that struck.

- How often are we all guilty of “fighting the last war”? Are we imaginative enough in the scenarios we consider when we build our Contingency Plans?

- The institutions and structures responsible for emergency planning were labyrinthine in their complexity.

- Peacetime corporate compliance checks and balances do not always translate well to the management of a crisis. Introducing multiple levels of sign-off approvals may just result in multiple potential failure points

- The UK government’s sole pandemic strategy …. focused on only one type of pandemic …

- An echo of the first point. In the oil and gas industry I do see a lot of attention (understandably) on loss of well control incidents, but this should not be at the expense of considering other incident scenarios in our planning.

- There was a failure to learn sufficiently from past civil emergency exercises and outbreaks of disease.

- Often our “lessons learnt” procedures actually just collect “lessons identified” and then fail to do anything about putting improved procedures in place to prevent the issues from re-occurring.

- … Despite reams of documentation, planning guidance was insufficiently robust and flexible … unnecessarily bureaucratic and infected by jargon.

- Impressed by how thick your Contingency Plan is? Think again!

Procedures need to be simple and quick to read and understand at 3am in the morning

- Impressed by how thick your Contingency Plan is? Think again!

- In the years leading up to the pandemic, there was a lack of adequate leadership, coordination and oversight.

- How engaged are your Executive Leadership Teams in the Crisis Planning and exercising process? Without senior-level buy-in and a commitment to learn the plan will fail.

- The provision of advice itself could be improved. ….. The advice was often undermined by ‘groupthink’.

- Why not nominate a “dissenter” in your team? It avoids the fear of getting labelled as ‘being awkward’ if you’ve been specifically asked to take on that role. However you do it, challenging our plans is crucial.

...and then the Recommendations:

- … government should create a single Cabinet-level ... committee ... responsible for whole-system civil emergency preparedness and resilience, to be chaired by the leader or deputy leader of the relevant government.

- Have we got very clear, senior-level crisis leadership structures which span our normal ‘peacetime’ functions and silos?

- The UK government … should develop a new approach to risk assessment that moves away from reliance on reasonable worst-case scenarios towards an approach that assesses a wider range of scenarios representative of the different risks and the range of each kind of risk. …

- Once more; the need to avoid focussing on just one ‘big’ risk; instead looking at a range of crisis scenarios

- (the) civil emergency strategy … should be subject to a substantive reassessment at least every three years to ensure that it is up to date and effective, and incorporates lessons learned from civil emergency exercises.

- Regular formal review of our plans and a positive focus on the learnings from exercises in incidents is the sort of Good Practice we all should embrace.

- The UK government … should hold a UK-wide pandemic response exercise at least every three years.

- What is your minimum Major Exercise frequency? Is it genuinely an exercise or is it more of a demonstration of capability and a tick in a box?

- Each government should publish a report within three months of the completion of each civil emergency exercise summarising the findings, lessons and recommendations, and should publish within six months of the exercise an action plan setting out the specific steps to be taken in response to the report’s findings.

- Holding ourselves to account to learn from our exercises, rather than mutual back-slapping at the end of an exercise is foundation for growth

- All exercise reports, action plans, emergency plans and guidance from across the UK should be kept in a single UK-wide online archive, accessible to all involved in emergency preparedness, resilience and response.

- How accessible to all our your exercise reports and findings?

- External ‘red teams’ should be regularly used … to scrutinise and challenge the principles, evidence, policies and advice relating to preparedness for and resilience to whole‑system civil emergencies. response.

- Independent external review of how we do our Contingency Planning and Preparedness which brings a challenge to our principles and policies is a great idea. Most audits only check that we are following our own rules; this is an opportunity to ask whether our own rules are worth following!

Out of Sight, Out of Mind

RIP: Rusting in Pieces

The world’s oceans and shorelines are at risk from an invisible foe.

According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), ‘marine pollution from sunken vessels is predicted to reach its highest level this decade, with over 8,500 shipwrecks at risk of leaking approximately 6 billion gallons of oil.’[1]

Large numbers of potentially polluting wrecks are casualties from wars, with tonnage sunk en-route to the UK in the Atlantic during the second World War, some 80 years ago, contributing significantly to these numbers. Corrosion of these vessels, coupled with increasingly active weather events means that the risk of catastrophic failure and hydrocarbon release is getting higher and higher.

[1] International Union for the Conservation of Nature; Issues Brief. April 2023 www.iucn.org/issues-briefs

[2] http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/150962.stm

[3] Managing Potentially Polluting Wrecks in the United Kingdom; P Hill et al. Threats to our Ocean Heritage: Potentially Polluting Wrecks, Ch 6; M Brennan ed. Springer Briefs in Archaeology 2024. ISBN 978-3-031-57959-2

[4] Risk Assessment for Potentially Polluting Wrecks in U.S. Waters; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 2013. https://nmssanctuaries.blob.core.windows.net/sanctuaries-prod/media/archive/protect/ppw/pdfs/2013_potentiallypollutingwrecks.pdf

[5] A Standardised Approach to the Environmental Risk Assessment of Potentially Polluting Wrecks. F Goodsir et al. Marine Protection Bulletin 142 (2019) 290-302

[6] Potentially Polluting Wrecks: defusing the ticking timebomb. Horizons; Lloyds Register Foundation. December 2023. https://www.lr.org/en/knowledge/horizons/december-2023/potentially-polluting-wrecks-defusing-the-ticking-timebomb/

[7] Assessment Methodologies for Potentially Polluting Wrecks: The Need for a Common Approach; M Lawrence et al. Ch 11; M Brennan ed. Springer Briefs in Archaeology 2024. ISBN 978-3-031-57959-2

Legislating for the Past

There is little in the way of international legislation to encourage active intervention in this pollution risk. The IMO Nairobi Wreck Removal Convention entered into force in 2015, but this only applies to wrecks occurring after this date. In any case, as is the norm for the IMO, the convention specifically excludes warships.

It is left therefore to the environmental conscience of states with an interest in Potentially Polluting Wrecks (PPW’s) as to whether they intervene or not.

Respect for the Fallen

It is easy to forget in our desire to protect the planet, that many of the PPWs are also the final resting place of brave seafarers. Before we rush in to save the oceans, we need to be certain that we are treating burial sites with the utmost respect. Some may remember the protests that accompanied the efforts to explore and raise parts of the Titanic for instance.[2]

SALMO to the Rescue

There are some examples of Governments taking the initiative in this arena though. The UK government as one of the largest ‘owners’ of PPW thanks to WWII has, to its credit, taken positive steps in this regard, led by the Salvage and Marine Operations (SALMO) division of the Ministry of Defence. The Wreck Management Programme was born in 2008 to proactively manage the environmental and safety risks associated with its remaining wreck inventory.[3]

Similarly, in the USA, Congress took a substantial step in addressing the public concern on this issue in 2010 when it directed NOAA to conduct an assessment of shipwrecks that could impact coastal and Great Lakes States.

Sea No Evil

In a year when over half the world’s population goes to the polls, there could not be a better time to get this issue firmly on every politician’s agenda. We need to see the subject of Potentially Polluting Wrecks not just on the agenda of the traditional Oil Spill conferences, but across a wider range of platforms where the subject can get air-time. If we don’t talk about it, we can be sure that the risks will not get addressed.

The NOAA report[4] in 2013, amongst other things, proposed a methodology for assessing the relative risks of PPW around the US seaboard. We have seen other methodologies suggested by, for instance, by the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (cefas) in the UK[5] These are both excellent frameworks and if we can converge on one shared approach that is accepted by all players it would be a great step forward.

A Coalition of the Willing

The Lloyds Register Foundation called for ‘a global coalition of experts to create technical standards and engage international bodies in order to enable a more strategic response to the challenge.’[6] This was echoed by the Waves Group, a specialist maritime consultancy in their contribution the Springer Briefs report.[7]

Some great work has been done by many people already. However, I remember back to Interspill 2006 in London when this was on the agenda and I worry about whether it’s seen as ‘old news’ now.

Old news it may be, but the risk is still with us and increasing each year.

Plugging the Tier 2 Gaps

In 2015 IPIECA and IOGP published their updated Good Practice Guide on Tiered Preparedness and Response.

This was a seminal document which challenged the practice of defining Tiers based on spill volumes and instead “promotes a model for defining the three tiers according to the resources[1] required to respond to the incident, not the scale of the incident itself .”

This approach is eminently sensible in that it removed somewhat arbitrary volumetric thresholds for the three Tiers. Instead it looks for a risk-based approach which considers not just the volume of oil spilt but also the oil type, location and local sensitivities.

The “difficulty” with this approach, such there is one, is that using a risk-based approach requires some thought and takes more explanation to regulators and other stakeholders than a simple volumetric calculation.

[1]When assessing the resources needed, we should consider personnel, equipment and other support needed to response to the incident.

There are many excellent examples of excellent application of this Good Practice around the world.

One can see a flow through the Tiers, dependent on the scale of the incident, for instance in Rotterdam port. Here multiple operators within the port area have their own on-site (Tier 1) capabilities, which are supported by a good local Tier 2 contractor based in the port and, over the Channel, OSRL stand-by with Tier 3 resources available for deployment.

We see a similar picture around the USA where there are many strong commercial and co-operative Tier 2 organisations which provide a bridge from the local Tier 1 resource to the National Tier 3 capabilities provided by MSRC.

This seamless picture, however, is not repeated everywhere

There are many cases where players, especially downstream entities, with significant nearshore risk in less developed countries may have a Tier 2 gap. The problem is that, for instance within a port, a relatively small spill can have immediate and significant consequences.

With the Tier 3 resources of OSRL 48 to 72 hours away, the local Tier 1 capabilities are quickly overwhelmed and there is often not much more in terms of Tier 2 to step into the breech.

I know from bitter experience that often the response is to push OSRL to respond more quickly or even to (for no additional cost of course) provide more local resources; basically asking OSRL to become a free Tier 2 service.

So how then can those holding the risk fill this potential Tier 2 gap?

For these locations the Tier 3 resource is almost always OSRL; and their capabilities and timescales for deployment are well defined. Operators can and should plan ahead to help OSRL speed up their deployment by working through the local logistics choke-points. Especially around visas/work permits for personnel and customs clearance for equipment. This may close the gap a little, but additional immediately-deployable resources will still be required.

There are a few possible solutions to filling the Tier 2 gap; all require a bit of work and some require funding too

Mutual aid is everyone’s first thought and, on the face of it, it is a low cost, simple option. Sadly, if it were easy, there would be hundreds of fully-functioning mutual aid arrangements in place all around the world. Look around and you’ll find that there are not.

For mutual aid to work, a series of conditions need to be met:

- Multiple local operators carrying similar risk profiles

- Those operators to have a similar motivation to close the tier 2 gaps

- A legal framework that provides suitable indemnities for all parties

- Someone who drives the agreements and ensures that they are regularly exercised

Before I left OSRL, they and Offshore Energies UK saw through a Mutual Aid Framework for the UK Continental Shelf operators. This was an excellent piece of work, but it took a lot of time and energy to get it over the line (massive kudos to Lucy Bly for this by the way).

If Mutual Aid isn't an Option, then what?

If the mutual aid conditions are not met, and I am thinking especially about downstream installations such as terminals which may be the only significant oil spill risk in a port, then another approach is needed. The options pretty much boil down to either:

- Build (fund) commercial Tier 2 capability; or,

- Build an in-house Tier 1 response which negates the need for Tier 2.

In most locations there will be waste management contractors, a vessel supplier or maintenance/general labour organisations that the risk holder can work with. The contractor will need help though in building oil-spill response capacity. They will need a contract term and renumeration that makes it economically sensible to invest in equipment purchasing and personnel training. They will also need contract conditions that do not saddle them with disproportionate levels of liabilities in the event of a spill response.

All of this is an anathema to many purchasing teams, but it is needed if the capacity is to be created.

The alternative is to invest in-house with additional equipment and more personnel training in oil spill matters. There is a direct financial cost to this as well as the opportunity cost of ‘distracting’ personnel from the day job and so diluting profitability.

In both cases the need for good quality training and regular exercising cannot be over-stated. As with the mutual aid option; what may sound easy and straightforward is far from it.

Whichever route is chosen; it requires funding where there was none before, which in a world of budget constraints, requires strong advocacy from a champion within the senior leadership of risk-holding organisation.

It is the job of the Emergency Response professionals to find the air time with and gain the commitment from these senior leaders to plug the Tier 2 gaps.

Exercise Is Good For You!

Why do so many companies exercise their Crisis Management and Incident Response plans so infrequently and so poorly?

Bold words, I know, but this is based on 20 years of attending exercises with companies, governments and response organisations. Don’t get me wrong; of course there are some great examples of Good Practice out there. But my experience of the majority of exercises, if they happen at all, is that they just do not hit the mark.

I think the underlying cause is borne of a fear of failure, or if not fear of failure just a concern about losing face in front of one’s peers.

It means that people put off having exercises; we’re too busy, we responded to a real incident last year, it will put too much stress on the team, we did a regulator exercise recently so don’t need to do an internal one as well.

(Regulator exercises by the way, are not really exercises if we are honest; they are a demonstration of capability which it is right and proper for the Regulator to expect. Truthfully though they are not a real stress-test of the Incident Management plan)

It is why senior leaders avoid taking their roles; “it would be good for a junior person to gain experience”, “I’ve got a migraine”,” I’ve got to deal with an urgent matter” etc.

It is why that people just make stuff up to deal with challenges (particularly around logistics) they are facing in the exercises. People, vessels and freight aircraft just seem to get magic-ed up out of no-where to solve the problems being faced. A three line email somehow deals with an inject about an NGO protest. Funds needed to support the response are instantly available from the nearest money tree.

This avoidance really frustrates me. Frankly, it amounts to cowardice. It even frustrated me when I was the Incident Commander in exercises at Oil Spill Response Ltd.

I remember well an exercise where an inject had a vessel casualty blocking the entrance to the port where our Capping Stack was going to be deployed from. I was just enjoying the challenge of finding a solution when overnight the SimCell told us that the vessel had been salvaged and all was well. I was genuinely disappointed to have that issue removed so easily.

As far as I’m concerned the best exercises use real-time, real-life data and have injects that make them tough as hell. “train hard and flight easy” is a great military maxim and it applies equally to Incident Management exercises.

If you happen to be a Star Trek fan, then think of the Kobayashi Maru simulation!

So what makes a good exercise?

The IOGP/IPIECA Report 515 gives Good Practice guidance on Planning and Developing your exercise scenario and injects etc. I feel it is a little light on the Conduct of the exercise itself however.

I strongly advocate using real time data, especially in relation to logistics. Just what is the global airfreight market on the day of the exercise?Exactly where are the support/deployment vessels that will be required going to come from? How long does it really take to obtain visas and work permits for the in-field team? Honestly, who is genuinely available and willing to be deployed in-theatre? These are the issues that trip of up in real events, so let’s play then for real in the exercise.

The team running the exercise must be ready with a stock of potential injects to keep the exercise moving and also, dare I say it, to put pressure on the Incident Command team. If the SimCell see a potential weakness in the response chain, they should be prepared to ditch their original exercise plan and drill down.

The aim of the exercise is not to catch people out of course, but it should explore every potential weakness in the Crisis Plan delivery, so that lessons can be learnt and the plan be made more robust. It is far better to “fail” in an exercise than to mess up in a real incident after all!

Recovery, Rest and Reflection

As we Christmas and a break from work for many of us, I thought now would be a good time to talk about Recovery, Rest and Reflection. Not least because I feel we sometime confuse these terms and I think we should be more deliberate in our work and home lives about the differences between these activities.

(I should say that dictionary definitions do not help us much as they vary and overlap, so I am making my own distinctions here.)

In this season of joy, make sure that despite the mayhem of food, family and fun, you are able to find the time to recover, rest and reflect....

Working long, high intensity, shifts in an Emergency Operations Centre there is little time for rest, but a great need for recovery between shifts in order to maintain energy and focus. A good analogy may be a decathlete who will go through a routine of warming down, ice baths, and massages between events. This athlete is not resting, but they are recovering in order to be ready for the next challenge. The same applies to an Incident Commander who may be working demanding shifts over a prolonged period; just as the athlete’s muscles suffer a build-up of lactic acid which needs to be removed so the human brain needs time to cleanse, re-order and repair. The magical solution to this is sleep! If you have not read Matthew Walker’s excellent book; Why We Sleep, then I recommend that you add it to your list for Santa to deliver this Christmas. Prioritising good sleep is a life-saver during a crisis.

Short breaks during our work day help enormously; even if it is just to walk down the corridor to grab a coffee. These breaks give space to pause, reflect and get your thoughts in order, and somehow walking helps that process. They are neither rest nor recovery, but these brief times of reflection give you super-powers through the incident.

To return to the sportsman/woman analogy; there are few if any sports that are played competitively all the year round. There is a close season for almost all sports and this is when athletes can truly rest, as opposed to just recovering. For us the holidays are our close season; so how can we use them best to rest?

Rest is a complete re-charge and re-set that allows you to return to work, or whatever you do in life, energised and full of great ideas. Rest can take many forms; for me, I love to walk for miles in the mountains, for others it may be reading, knitting, listening to music, gardening or cycling. It can be physical, it can be cerebral; but whatever form it takes, rest is about switching off from work and finding purpose in other things.

During these times of rest, there is also the opportunity for deeper reflection. If you are someone who meditates, prays or practices mindfulness then this may come quite naturally, but taking time to “be” and not to worry about work issues, but to let your mind process those challenges you may be facing is so important. It requires some detachment to avoid spiralling into worry or self-flagellation. One antidote to this is to view yourself and the situation as a third party, dispassionate, observer. However you do it though, these times of deep reflection are vital if you are to grow as a person.

Pitch Perfect Process

I do love a good bit of process. Process helps to keep us safe, it helps protect ourselves and our businesses from liabilities, it offers us reassurance that we are doing the right thing.

There’s all sorts of reasons why process is good. Process though, has its risks; especially in a Crisis situation. The two process problems that I have often encountered in Emergency Operations Centres during live events and in exercises are:

1. Becoming fixated on process at the expense of managing the incident; and,

2. Using processes that work in the routine business environment but are not helpful in managing a dynamic incident

Process Fixation

It really is so easy to become lost in process; and I would argue that this may be of either of two reasons.

The first is that process can become a means by which difficult decisions are avoided. In a crisis situation an Incident Commander rarely has all the information that they would like available and so has to trust their judgement a lot more than they would in the normal business environment. Process tends to demand data and want certainty.

We do not have the luxury of time in an emergency and so have to make decisions before all the data is available. Incident Commanders who are not comfortable with this uncertainty will tend to avoid making the decision by demanding more data and so an infinite do-loop of information requests and clarifications ensues. A wise colleague of mine always preached that “any decision is better than no decision” and this advice remains sound today.

The second reason we sometimes get lost is process is in our desire to deliver the product possible. The same consultants that produce our 1,000 page Contingency Plans (yes I know I’m exaggerating) in peacetime can become absorbed in producing Incident Action Plans of the same depth; fully justifying every recommendation therein with reams of supporting information. Voltaire told us that “the Perfect is the Enemy of the Good” in the 18th Century and he was right.

Process Overlay

Sound Corporate Governance and strong Compliance Cultures are, rightly, drilled into all us and so our businesses all have many layers of legal, financial and quality procedures to keep us safe, protect our company’s reputation and financial position. The problem comes when these procedures are brought into the Emergency Operations Centre and imposed on the Crisis Management procedures already in place. The risk here is that the very review and approvals processes which, with an abundance of good caution, protect our businesses in steady state will slow down or even prevent decisions being made in a timely manner. Perversely, the corporate checks and balances that protect the financial and reputational well-being of a business in the steady-state environment, can result in reputational and financial damage during a crisis. Slow decision-making will burn through cash and impact negatively on the reputation of a business, that will be portrayed as fiddling whilst Rome burns.

What does Good Look Like?

Atul Gawande in his excellent book The Checklist Manifesto[1], makes a distinction between the steady state, routine scenario of a DO – CONFIRM checklist, versus a dynamic, emergency situation of a READ – DO checklist. The point he makes is that we need different (and shorter) processes in an emergency than we do in the routine world. In a crisis we need to react quickly to recover and our standard business models with their, often lengthy, procedures and sign-off requirements are simply not nimble enough to cope in a very dynamic environment.

Why not challenge yourself and your team to develop Crisis Management procedure that distil down to:

- A Role Card,

- a Flowchart; and,

- a couple of “READ – DO” Checklists

…for each role in the command team?

It may sound scary, especially to your Quality Managers, but really are you going to read the 10 page (or even 10 paragraphs) introduction to your Crisis Management Plan when you walk into the Emergency Operations Centre?

If we keep it simple, then we give our incident command teams the handrails they need at 2am in the morning without wrapping them in red tape.

What is more important, however, than the right procedures; is the right people. Good people will manage an incident despite poor procedures, but poor people will fail in a crisis even with good processes. More on that later…….

[1] The Checklist Manifesto. Atul Gawande. Profile Books. ISBN: 978-184668 3145

The Curse of Complacency

Over-reliance on engineering design and business continuity processes can lead to over-confidence around Crisis Management scenarios for Governments, industry and other enterprises. Worse still, push-back against lobbyists make even make it difficult to admit that crises could ever occur. How then do Crisis Management / Emergency Response professionals engage with senior leaders to prepare for Black Swan events?

Engineered Out

Back in the day, I was responsible for the safety case for a major new civil nuclear facility. Working with the engineering design team, we poured over the process flow diagrams, piping and interlock drawings and all the other design documentation. I ran HAZID’s and chaired more HAZOP’s than I care to remember. With my team, I developed insanely detailed fault trees for ever risk scenario we had identified and dug through reems of tribology and other historic failure data to generate probabilistic safety assessments. Then we would undertake critical path analysis to identify weaknesses in our safety barriers and either engineer them out or add additional mitigations. After all this I ran a Failure Modes and Effects Analysis process for every engineering drawing to make sure that the HAZOP had not missed anything. Once complete, I proudly presented my Fully Developed Safety Case to the UK Nuclear Installations Inspectorate, who accepted that the risks from the facility were “As Low As Reasonably Practical” and the facility went ahead.

Never at any stage did I think of any Crisis Management / Emergency Planning scenarios. I was so confident in the engineering design, that it never crossed my mind that there could be any meaningful radioactive release from “my” plant.

I now hang my head in shame thinking about my over-reliance and blind confidence in engineering design.

Perfectly Mitigated

More recently, I was involved in a Crisis Management exercise for a cyber attack scenario. Our story-board had a hacker who had gained access to admin passwords deep in the Company’s system and had launched a ransomware attack. The crisis team looked at how they could run the business on good old pen and paper and, if they could, for how long. Meanwhile the IT team told us not to worry as they just has to roll back the system to the day before the ransomware note, re-install and we’d be back up and running within 48 hours. With respect to any personal and financial data that might have been accessed, the IT team told us that this was impossible due to the Multi-Factor Authentication in place.

As gently as I could, I pointed out that they did not know how the hacker had accessed the Company’s data and how long they had been in there. Simply rolling back to the previous day’s data risked leaving the same entry point still available to the hacker, who could in any case have made themselves a few other access points whilst they were there, potentially including a way of spoofing the MFA processes. It could well take weeks of forensic analysis to find the entry point that the hacker found and close it, meanwhile re-installing peta-bytes of information from the cloud would also take weeks not days. As a result the IT infrastructure could be down for a month or more, not the 48 hrs claimed.

I do not believe that the IT team were deliberately lying here; but in a major exercise with the Company’s senior leadership team, they were so keen to make a good impression and demonstrate their competence that they found it hard to admit that actually the Company could be off-line for weeks if not months in this scenario.

It Could Never Happen Here

The many and various anti-industry and NIMBY pressure groups are also pushing Companies, at a senior level, to use that dangerous word; “never”. There is a potentially counter-productive feedback loop, where the anti lobbyists exaggerate the risk of the new nuclear facility, the proposed fracking campaign or the expansion to the Xylene process train. The more that these lobby groups shout about the risks, the more the spokespersons for industry play them down. The worry as these debates escalate is that the senior leaders within industry begin to believe their own publicity or, more insidiously, decide that these risks should not be recorded on their Risk Register as such a document may be “discoverable” by the anti lobbyists, who would then hold it up as proof of the danger of the plant.

Whilst I have no evidence of this extreme of thinking, I do recall vividly an inland well blow-out (or loss of well control incident, to give it its formal title) for a former Soviet well being run by an SME which I attended. On return, I happened to be speaking to a senior leader of a major IOC and suggested that it would be good to run a crisis management exercises with them around a similar incident. His response was that no IOC would ever have a well blow-out; the engineering design, process safety and blow-out preventer technologies were such that such an incident would never occur.

Sadly, we know what happened for one major IOC a few years later in the Gulf of Mexico….

The Need For Challenge

So how then can Crisis Management professionals get the attention of senior leaders in their organisation without sounding like Chicken Licken shouting that the sky is falling down?

Where we can point to incidents that have occurred in other companies or near misses that could have resulted in emergencies for our own, that helps. It is evidence-based and hard to argue with; loss of well control incidents are now very much on the agenda for all oil & gas companies now for instance. There is still the risk of ‘it couldn’t happened here’ as a response though; the Chernobyl melt-down can be dismissed as arrogant Russian technocrats undertaking unsafe experimentation on a dodgy RMBK reactor – it could never happen in a western-run PWR could it now?

We can argue that by playing out a worst-case risk we can find out much about all levels of our preparedness. Talking about the importance of thinking through “Black Swan” events may offer a soft way in.

When participants in an exercise drift into the Harry Potter school of Crisis Management with overly-simplistic and/or barely credible responses, we need to be prepared to challenge vigorously but respectfully. Put on your auditor hat and probe the rigour of the solutions proposed and, if needs be, call out any prevarication from your participants

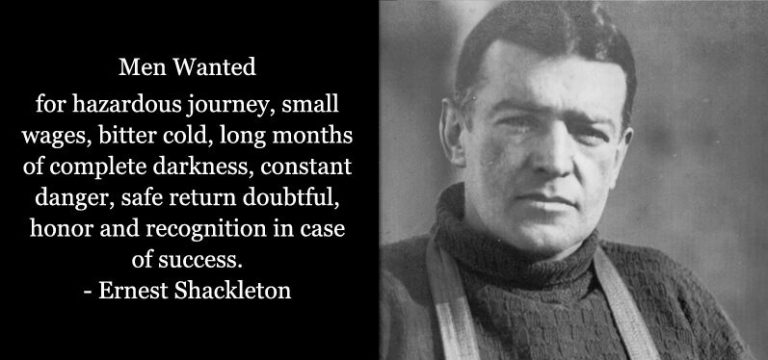

“.... if I am in the devil of a hole and want to get out of it, give me Shackleton every time"

Was Shackleton Really A Great leader?

September 2023

Let me start with a confession; I am a massive Ernest Shackleton fan-boy. I have an entire library of books about Shackleton and his unbelievable achievements leading the ill-fated Imperial Tans-Arctic Expedition to Antarctica. Trapped in unexpectedly heavy pack-ice in the Antarctic summer in January 2015 the boat was eventually crushed and sank. Shackleton kept his team safe and well on the ship and then on the ice pack and, via an amazing voyage in a life-boat to South Georgia, eventually all the party were rescued without a single loss of life 18 months later.

Shackleton is often quoted as an example of exemplary leadership. Indeed, my alma mater; the Henley Business School use one of my favourite books on Shackleton’s leadership: Leading at the Edge (Dennis N T Perkins, HarperCollins 2018) on their Leadership courses. But is he really the leadership model that we should all aspire to?

Manger, Leader or Something Else?

One thing is crystal clear from all the books on Shackleton; he was supremely unsuccessful in his life away from the Antarctic. He jumped from job to job and was consistently poor in all of them, eventually dying heavily in debt as he headed out on another Antarctic expedition where maybe he hoped to recover his lost glories.

By any modern definition, Shackleton was a pretty poor manager. He was unwilling or unable to use established processes when given to him, for instance with Robert Scott in a Royal Navy management structure on the Discovery expedition. He hired on the basis of whether he liked the look of a man, not on basis of their skills, experience (or for that matter their psychometric profile and the results of an assessment centre). He was often self-absorbed, he made many enemies and he was disinclined to share his knowledge with others.

Yet still, I love him.

Although Shackleton is much vaunted as an exemplar of leadership, I am far from convinced that the traits he showed are those exhibited by the senior leadership teams in many large organisations. Surely the mark of a great leader would be to bring success to the ventures they were involved with; improving shareholder value, generating a strong cashflow, winning awards and so on. The truth is that he never did that. He did manage the persuade a number of wealthy patrons to invest in his ventures, but they saw little return on investment, unless one counts having a glacier named after you as a good use of your cash. By most objective measures, Shackleton was really a bit of a failure as a leader.

Despite this, I think he is a great role model.

The reason that I admire Shackleton and reference his leadership style in training is summed up by a quote from Apsley Cherry-Garrard, a contemporary of Shackleton’s in the polar expedition field. He wrote “For a joint scientific and geographical piece of organisation, give me Scott; for a Winter Journey, Wilson; for a dash to the Pole and nothing else, Amundsen: and if I am in the devil of a hole and want to get out of it, give me Shackleton every time"[1]. This is what makes Shakleton so special; he was not a manager, he was even not really a leader; but he was the best Incident Commander in a crisis that you could wish for.

[1] Wheeler, Sara. Cherry: A life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard. 2001: Jonathan Cape.

The Great Incident Commander

Many books have been written and careers built on taking about the differences between management and leadership, but few about the difference between the steady-state of managing/leading an organisation and the highly dynamic challenge of leading in a crisis. In any organisation, and especially large organisations, we rely (quite rightly) of having strong processes to guide our activities. Truthfully the line between management and leadership is blurred in these organisations, as the people referred to as ‘senior leaders’ have in most cases got to that position because they have been excellent in how they have implemented management processes as they have climbed through the ranks. This can mean that in a crisis, these same people may be tempted to go back to the “safe space” of process when confronted by the challenges of VUCA[2] world.

Process, of course, has an important role to play in managing a crisis; it offers us a handrail, it helps us control our limbic freeze/flight/flight reflexes, it provides us with checklists and other helpful tools. A crisis/incident management process which we are familiar with and have trained against gives any organisation a firm foundation on which to build their response.

If we stop there, however, we are missing a critical success factor in delivering a safe and successful response. Those managing (or should I say, leading?) the response need to model many of the traits that Ernest Shackleton showed over one hundred years ago. Perkins[3] distilled Ten Strategies for Leading at the Edge from his analysis of Shackleton and I highlight eight of these here that I think should be learnt by a potential Incident Commander / Crisis Manager.

[2] VUCA: volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity

[3] Perkins, Dennis. Leading at the Edge. HarperCollins 2018

- Victories and Vision. Never lose sight of the ultimate goal but focus energies on short term objectives

- Personal Example.

Set a personal example with vivid symbols and gestures - Balanced Optimism.

Instil optimism and self-confidence but stay grounded in reality - Personal Stamina.

Take care of yourself; maintain your stamina and let go of guilt - The Team is Everything. We are one, we succeed or fail together

- Lighten Up.

Find something to celebrate. Something to laugh about - Risk.

Be willing to take a risk and make a decision - Tenacious Creativity. Never Give Up; there’s always another move.

Too often I have seen exercises and live incidents become absorbed in process, rather than having a clear ‘end-point focus’ (point 1) which required decision-making (7). Often teams become trapped in the repeated use of a single strategy which is clearly not working (8), rather than improvising and trying something different. Maintaining a calm and optimistic mindset (3, 6) has a disproportionate impact in a crisis; if the Incident commander is assured and confident, then so is the team. The team, though, is everything and the Incident Commander is only as good as their team, so they need to be clearly part of it (2, 5). Finally the need to manage yourself and your emotions (4) is often overlooked. How you manage your own mindset in a crisis makes a huge difference to the outcomes.

In a crisis, it pays to be more Ernest.

Haunted by Ghost Ships

August 2023

The risk of a spill in the Mediterranean is increasing - are we prepared?

Russia Rewired

Just 18 months after the invasion of Ukraine and the application of sanctions by Western governments, exports of Russian crude oil and refined products such as Diesel and Heavy Fuel Oil are back at pre-invasion levels (Source: Bruegel). What has changed though is the destinations, means of transportation and distribution. These changes have resulted in an increased risk of oil spills, which needs to be addressed.

Crude oil is mainly heading to India and China with Turkey a close third (Source: CREA). Meanwhile, according to Energy Intelligence, North Africa and Turkey are favourite destinations for Diesel, whilst Asia and the Middle East are the top destinations for Heavy Fuel Oil.

Cargoes are not all travelling direct to these locations however. Smaller shipments are sailing from the Russian Baltic and Black Sea ports to meet VLCCs where Ship-to-Ship (STS) operations are being undertaken to bulk up the cargo for onward transportation.

This is not done for purely commercial reasons though; these vessels are frequently sailing under false names, and without their AIS locator switched on. The STS operations are taking place in international waters away from any Nation States’ jurisdiction. All in order to hide the cargoes from sanctions.

Holidays in the Sun

Three areas of the Mediterranean Sea are hot spots for these questionable activities; offshore Greece, Offshore Malta and around the Straights of Gibraltar. The Marine Executive and Lloyds List tell us that Vessel Management companies domiciled in Greece, Dubai and India have suddenly acquired large fleets of tankers. More than 440 tankers above 30,000 dwt tonnes, with an average age of 20 years old (which would normally mark the retirement age for a tanker) have been identified as solely deployed for these operations; an increase of 180 vessels in the last 12 months . Less than half of these vessels have insurance via the International Group of P&I Clubs, rather they have Russian or Indian cover of sometimes dubious strength. The degree of vetting prior to chartering is also up for debate.

The IMO is doing what it can, but as a UN Organisation which still includes Russia and her supporters within the family, it is limited in what it can do. The worry from the IMO is that this could also result in a participating shipowner evading its liability under the relevant liability and compensation treaties (e.g. International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (CLC) and the International Convention on Civil Liability for Bunker Oil Pollution Damage (Bunkers Convention)) in the case of other ships, placing also an increased risk on coastal States and the International Funds for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage.

All this serves to increase the risk of crude and HFO spills in the Mediterranean. Although international efforts continue, there is little immediate prospect of reducing the risk, so our focus should be on mitigating the consequences of any incident.

A Mediterranean Mess?

Whilst this trade continues the oil spill risk to the coastlines of all Mediterranean states, but especially Greece, Malta, Morocco, Spain and Gibraltar is increased. Worse still, there is a high likelihood is that there will be no easily identifiable Responsible Party or that if there is there will not be adequate insurance cover from the Ship Owner nor from International Conventions. These nations now face the real prospect of a crude or HFO spill impacting their waters and polluting their coastlines with the responsibility and cost of clean-up falling solely on the National Competent Authorities.

With support from REMPEC, West MOPoCo reported on the state of oil spill preparedness in the Western Mediterranean and, once any political gloss is removed, it does not make great reading for states such as Malta and Morocco. Whilst Spain and Gibraltar, for instance, both have the financial means and the incident response structures to respond (not least with Membership of Oil Spill Response Ltd), there are certainly gaps in the ability of many Mediterranean states in their ability to respond to an incident; especially if those states have to bear the costs of the incident management themselves.

We should not, either, rely on International Offers of Assistance to solve the problems in the event of a spill. The idea is great of course, but generally this provides additional expertise and maybe some spare equipment. It does not give deep pools of people and equipment and nor is it a solid funding mechanism.

Meanwhile, according to the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, surface temperatures in the Mediterranean are at unprecedented highs. Whilst this may be great if one is swimming on the Costa Brava, these high surface temperatures provide the energy for more and more intense storms (see for instance the New Scientist).

Hope is not a Strategy

We are, potentially, looking at the perfect storm of an elderly vessel, with no meaningful insurance, being hit by a significant weather event during loading operations. Worse still the ensuing oil spill then polluting the beaches of a Nation that is ill equipped to deal with it and has insufficient funds to call in third party resources.

How then can we be ready?

Projects such as West MOCoPo address generic concepts in preparedness, but with a real and present danger of spills from an unknown or un-funded Responsible Party, it is time to develop and test some more specific and realistic Worst Case Scenarios to test the continency planning and preparedness of those states at risk. IMO, UNEP and REMPEC all have a part to play here is supporting these efforts with in-kind help and, maybe, targeted funding. The lesson of FSO Safer; where the UN family saw a threat and moved pro-actively to address it, rather than waiting for a oil spill to occur, is a great example of how this can work.

Certainly, National Oil Spill Contingency Plans need to be updated, fully resourced and stress-tested to ensure readiness. Regular and realistic National Exercises need to be undertaken to tease out every potential crack in the plans and find solutions. In these exercises, political posturing needs to be put on one side; National Competent Authorities must be prepared to say that “we are not prepared”, otherwise no progress will be made.

The energy industry have a part to play here, just as they did with FSO Safer with both pro-bono support and funding where it is needed. Operators in the waters of states at risk may feel a particular desire to help as part of their ESG efforts.

The threat is real; let’s not just stand by with our fingers crossed.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.